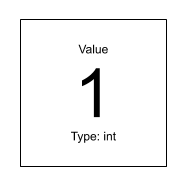

11Everything in Python is an object. An object is an entity which has a value, a type, and a unique identifier. For example, the number 1 we used in our arithmetic calculations is actually an object. It has the value 1 and the type int (which means integer number). Here are a few additional examples of objects:

112.152.15"Hello world!"'Hello world!''3''3'As we already know, Python outputs the value of the last command automatically in the REPL (the interactive interpreter). That’s why we know the value of the 1 object is 1, and the value of the "Hello world!" object is 'Hello world!' (never mind the different quotes for now, we’ll discuss these so-called strings in a later chapter).

To find out the type of a given object, we can use the built-in type function as follows:

type(1)inttype(2.15)floattype("Hello world!")strtype('3')strApparently, integer numbers are of type int (integer number), decimal numbers are float (floating point number), and character strings enclosed by single or double quotes are str (string) objects.

Conceptually, we can think of an object as an entity of a specific type with a specific value living in the computer’s memory:

Each object also has a unique identifier. We can use the id function to find out:

id(3)4411151376id(4)4411151408The actual identifier numbers are irrelevant (and probably different on your computer). The only thing that’s interesting about these identifiers is whether or not they are identical. In the previous example, the object 3 has a different identifier than the object 4, so we know that these are two different objects.

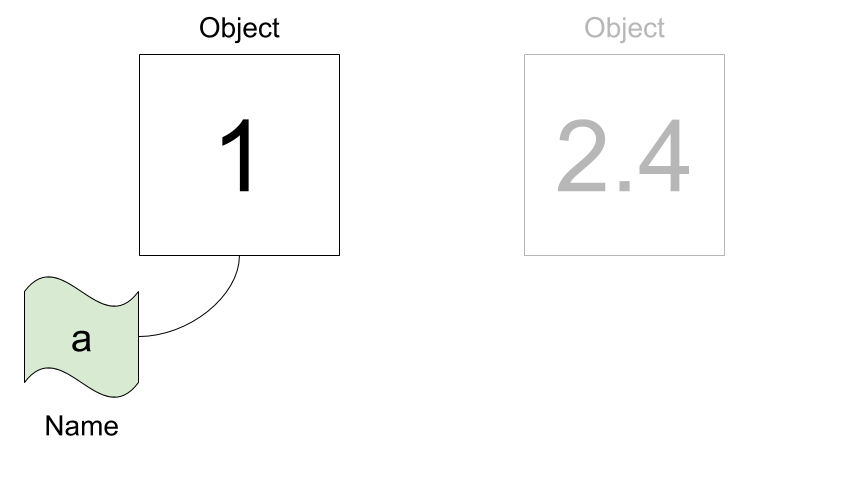

Objects can have names (in other programming languages, names are often called variables). We can assign a name to an object with the assignment operator = as follows:

a = 1This attaches the name a to the object 1 (of type int). We can visualize names as tags or labels attached to an object.

a is attached to the object 1. Another object 2.4 does not have a name.Python lets us reassign an existing name to a different object. Notice how the object on the left does not have a name anymore after we re-assign a:

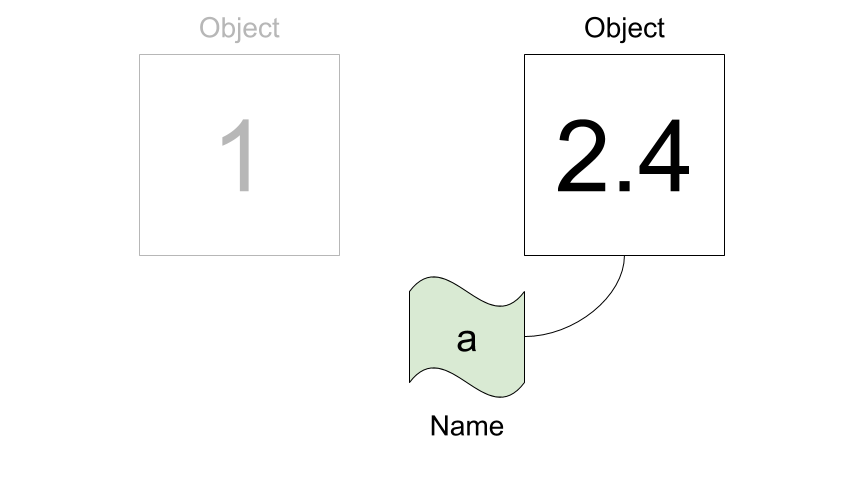

a = 2.4

a is attached to the object 2.4, and the object 1 does not have a name anymore.An object can also have more than one name attached to it:

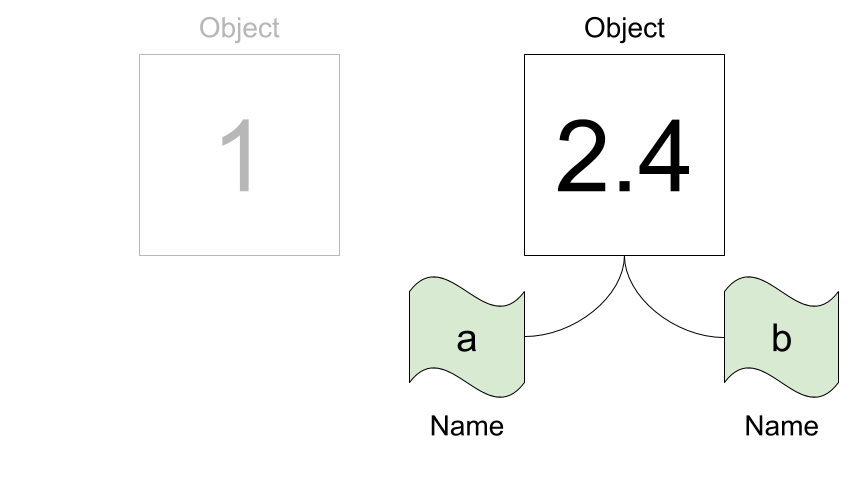

b = a

2.4 has two names a and b.We can confirm that a and b point to the same object by inspecting their corresponding identifiers:

id(a)4428706480id(b)4428706480Indeed, they are identical, so there is just one object with two names. If we want to check if two names are attached to one and the same object, we can also use the is keyword as a shortcut:

a is bTrueThe type of a name corresponds to the type of the object the name is attached to:

type(a)floattype(b)floatWhenever Python works with a name, it always replaces it with the value of the corresponding object. Furthermore, Python always evaluates the right-hand side of an assignment first before assigning the name. Consider the following example:

x = 11

9 + x # x is evaluated to 11, then 9 + 11 is evaluated to 2020After this line, x still has the value 11:

x11We now reassign the name x to a different object 2:

x = 2

2 * x # x is evaluated to 2, then 2 * 2 is evaluated to 44After this line, x has the value 2. However, we can reassign x again and even use the old value of x in the right-hand side of the assignment:

x = 2 * x # first evaluate the right-hand side to 2 * 2 = 4, then assign x = 4

x4Valid names can contain letters (lower and upper case), digits, and underscores (but a name cannot start with a digit). PEP8 lists recommendations for choosing good names – we only need to remember one rule for now: almost all names should be lowercase, and if necessary can also contain underscores, such as lower_case_with_underscores.

Names should convey meaning, so instead of a generic x or i, we should try to find a name that tells us something about its intended use. Also, it is good practice to use English (and not e.g. German) names, because you never know who will read your code in the future.

Here are a few examples for naming an object which represents the number of students in a school class:

number_of_students_in_class = 23 # too long

NumberOfStudents = 23 # wrong style, not separated with underscores

n_students = 23 # pretty nice

n = 23 # probably too short (but may be OK sometimes)Python defines several reserved keywords that are a core part of the language. They cannot be used to name objects, so it is important to know what they are. The following code snippet produces a list of all keywords:

import keyword

keyword.kwlist['False',

'None',

'True',

'and',

'as',

'assert',

'async',

'await',

'break',

'class',

'continue',

'def',

'del',

'elif',

'else',

'except',

'finally',

'for',

'from',

'global',

'if',

'import',

'in',

'is',

'lambda',

'nonlocal',

'not',

'or',

'pass',

'raise',

'return',

'try',

'while',

'with',

'yield']For example, this means that you cannot use the name lambda. If you do, Python will generate an error:

lambda = 7Cell In[25], line 1 lambda = 7 ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax

Python also has a number of built-in functions that are always available (without importing). Although it is possible to assign the names of these built-in functions to other objects, it is considered bad practice, because it might lead to subtle bugs. The following code generates a list of all built-ins:

dir(__builtins__)If you really want to use a name that is already taken by a built-in function, it is better to change the name slightly by appending an underscore. For example, instead of using lambda, you could use lambda_.

In general, operators work with objects. We have already used several (arithmetic) operators such as +, -, *, /, **, //, and %. Some operators are binary and require two operands (for example, the multiplication 2 * 3), whereas other operators are unary and require only one operand (for example, the negation -5).

An expression is any combination of values, names, and operators. Importantly, an expression always evaluates to a single value (or short, an expression has a value). Here are a few examples for expressions (remember that their values are automatically printed in the REPL):

17 # just one value1723 + 4**2 - 2 # four values and three operators37n = 25 # an assignment is not an expression!n # one name (evaluates to its value)25n + 5 # a name, an operator, and a value30Python reduces an expression to a single value. A more complex expression is evaluated step by step according to operator precedence rules (think PEMDAS) from left to right. As we’ve already discussed, Python evaluates the right-hand side of an assignment first before assigning a name.

A statement is a unit of code which Python can run. This is a rather broad definition, and statements therefore include expressions as a special case (in other words, an expression is a statement with a value). However, there are also statements that do not have a value, such as an assignment. Here are two examples for statements that are not expressions:

x = 13

print("Hello world!")Hello world!Note that although the print statement generates output, this output is not its value (try assigning a name to the function call)!

Determine if the following names are valid, and if they are, decide if they comply with PEP8 conventions. Describe whether each name is a good name for an object containing a string or an integer number.

2x_x23_namealphalambdaNameX2sumtest-caseConsider these three assignments:

width = 17

height = 12

delimiter = "."Determine both the value and type of the following expressions:

width / 2height / 3height * 3height * 3.0delimiter * 52 * (width + height) + 1.512 + 3"12 + 3"Calculate the area and volume of a sphere with radius r, area, and volume to compute these quantities. The number math.pi after running import math.

What is the type of the value True? What is the type of the value 'True'? What is the type of math (which you imported in the previous exercise)?

This document is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 by Clemens Brunner.

This document is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 by Clemens Brunner.